Kunal Arya’s electric scooter stuttered when he first tried to zip down the Hisar roads in 2019. India was yet to pave the way for a smooth ride for green mobility. Policy announcements spoke of the future, startups pitched grand visions, and global investors were beginning to zero in on the sector. But on the ground, the experience seemed messy.

Batteries were not new to Arya, thanks to his family’s inverter battery business, which was deeply embedded in India’s power-backup ecosystem. What was new was the sudden surge in demand for electric two-wheelers sold through small dealerships – often with limited understanding of long-term maintenance, component durability, or after-sales obligations.

“I entered the EV space as a dealer, not as a founder,” recalled Arya. “That meant I faced customers directly when something went wrong.”

In 2021, Arya was one of the earliest in a market that zoomed to 12.80 Lakh units at the end of 2025. Despite his initial success as Hisar’s top dealer of Yo Bikes, one of India’s early-day electric two-wheeler brands, there was a sense of unease. Most scooters were imported directly from China with minimal localisation. Breakdowns were rampant, spare parts were slow to arrive, and when customers were unhappy, it was the dealer – and not the brand – that had to face the flak.

“The scooters sold because people trusted us, not because the products were great,” Arya said. “But such trust is always fragile.” A network of 25 dealers of e-bike batteries that he ran parallel in Haryana gave him a broader view of the ecosystem. He saw dealers were struggling with the same issue everywhere – unreliable suppliers, inconsistent quality, and a lack of long-term support.

What troubled him most was that many EV brands operating at the time were not manufacturers at all. They were traders – importing scooters, rebadging them, and pushing them into the market with little accountability. “That’s when I realised that electric mobility was not failing,” he said. “The system around it was.”

It was too early to estimate the potential of green mobility in India, but Arya smelt the prospect, given the evolving dynamics in global markets. Today, India’s $2.13 Bn electric vehicle (EV) market is accelerating at 29.09% a year to unfold a $21.2 Bn opportunity by 2033.

A trip to China in 2021 brought the budding entrepreneur closer to the ecosystem. He spent time understanding components, failure points, and design limitations. Instead of looking for shortcuts, he started wondering what it would take to build an electric scooter fit for the Indian roads, Indian usage patterns, and Indian expectations.

When he returned, his decision was clear. Arya would not continue as a dealer in a fractured system. Instead, he would try to build a brand with the fundamentals fixed.

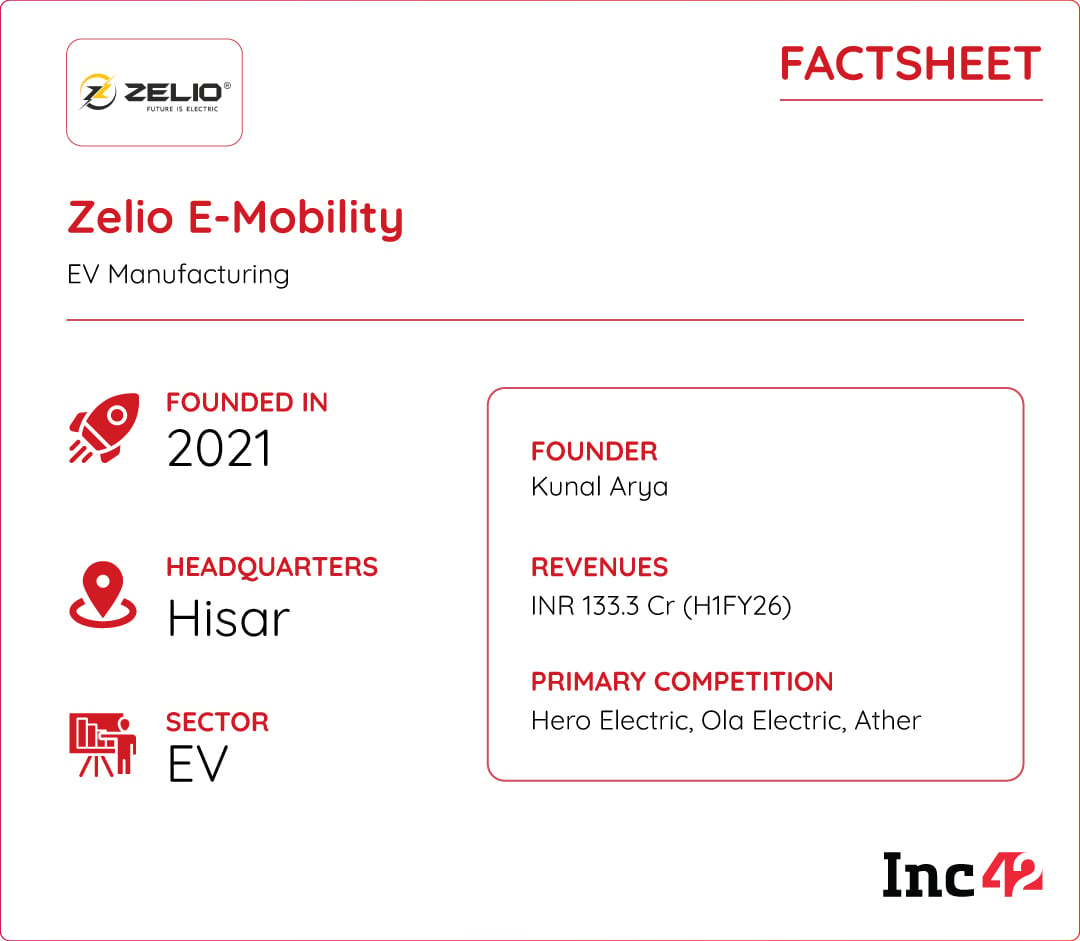

Zelio E-Mobility was incorporated later that year. “My aim was never to buy and sell,” he said. “I wanted to build. I wanted control over quality.”

Choosing The Unflashy Segment

At a time when most EV startups were chasing urban, high-speed electric scooters, Zelio took the road less travelled. It targeted the low-speed electric two-wheeler segment where vehicles are capped at 25 kmph that do not call for a driving licence or registration or insurance. On paper, it was a less glamorous market. In reality, it was vast and underpenetrated.

Low-speed scooters serve a very different customer base, compared to that for premium EVs. Most buyers are students commuting short distances or elderly users running daily errands or women seeking ease of use and households in Tier II and III cities and in rural areas where affordability and simplicity matter more than acceleration or app connectivity.

Zelio’s scooters are priced between ₹40,000 and ₹55,000 – less than half the cost of most high-speed electric scooters. That pricing, Arya said, is not a marketing tactic but a reflection of the market he understands. “In smaller cities, people don’t want features they won’t use,” he explained. “They want something that works every day and doesn’t cost much to run.”

This focus allowed Zelio to scale without stepping into direct competition with well-funded players like OIa Electric, TVS Motor (iQube), Ather Energy, Bajaj Auto (Chetak), and Hero Electric. These companies dominate the $1.6 Bn two-wheeler EV market in India that’s speeding up 28.34% annually.

Zelio vroomed into the market from Haryana and reached out to seven states within its first year. By 2023, it expanded to 18 states. Today, Zelio operates across more than 25 states, served by a dealer network of over 300 partners.

It’s not about expansion alone that played behind Zelio’s success, it’s more about continuity, as the founder says. Dealers who joined Zelio in its early days are still part of the network – a rarity in an industry known for its high churn rates. “That’s because we never treated dealers as replaceable. If a dealer succeeds, the brand succeeds.”

Unlike many EV startups that push one or two flagship models, Zelio built a broad portfolio early on. Today, it offers more than a dozen models tailored to different age groups and use cases – from GenZ-focussed designs to sturdy builds for older riders.

In 2023, Zelio took a step further to reinforce the trust it had built. It doubled the warranty on key components such as motors and controllers from one year to two years – an unusual move in the low-speed EV segment.

“We didn’t do this for marketing,” Arya asserted. “We did it because we were confident in our build.”

Getting The Economics In Place

Zelio’s evolution from a dealer-driven business to a manufacturing-led company was neither immediate, nor easy.

In its early years, like most players in its league, Zelio relied heavily on imported components. But as volumes increased and geographic reach expanded, the limitations of this approach became clear. Import dependence meant longer lead times, exposure to currency fluctuations, and limited control over quality.

By 2023, Zelio began developing its own models and working closely with Indian vendors to localise components. Today, around 20–30% of its sourcing is local. Over the next three years, the company aims to increase localisation to 70–80%.

To support this shift, Zelio set up a six-acre manufacturing facility in Hisar with an annual capacity of 72,000 units. The plant handles assembly, testing, and quality checks, while also serving as a base for future expansion.

Additional manufacturing units are planned in Odisha and other regions to reduce logistics costs and improve turnaround times. Zelio is also building a separate facility for its three-wheeler business under the ‘Tanga’ brand.

The move into three-wheelers reflects a broader evolution in Zelio’s strategy. While personal mobility remains the company’s core business, it has begun preparing for commercial use cases – delivery partners, shopkeepers, and small businesses.

Its recently launched Logix model targets this segment directly. According to Arya, the economics are straightforward: compared to petrol vehicles, fuel savings alone can recover the cost of the scooter within two years. “This segment doesn’t care about design or speed,” he said. “It cares about cost per kilometre.”

Balancing Profitable Growth With Scale

One of the most unusual aspects of Zelio’s story is its financial discipline.

In India’s EV ecosystem, which is often defined by cash burn and subsidy dependence, Zelio has maintained consistent margins. Over the last four years, it has reported gross margins of around 20%, EBITDA margins of 11–13%, and net margins close to 9%.

As volumes increased, cost-efficiencies were not used to inflate profitability, but reinvested into research and development, manpower, and manufacturing capacity.

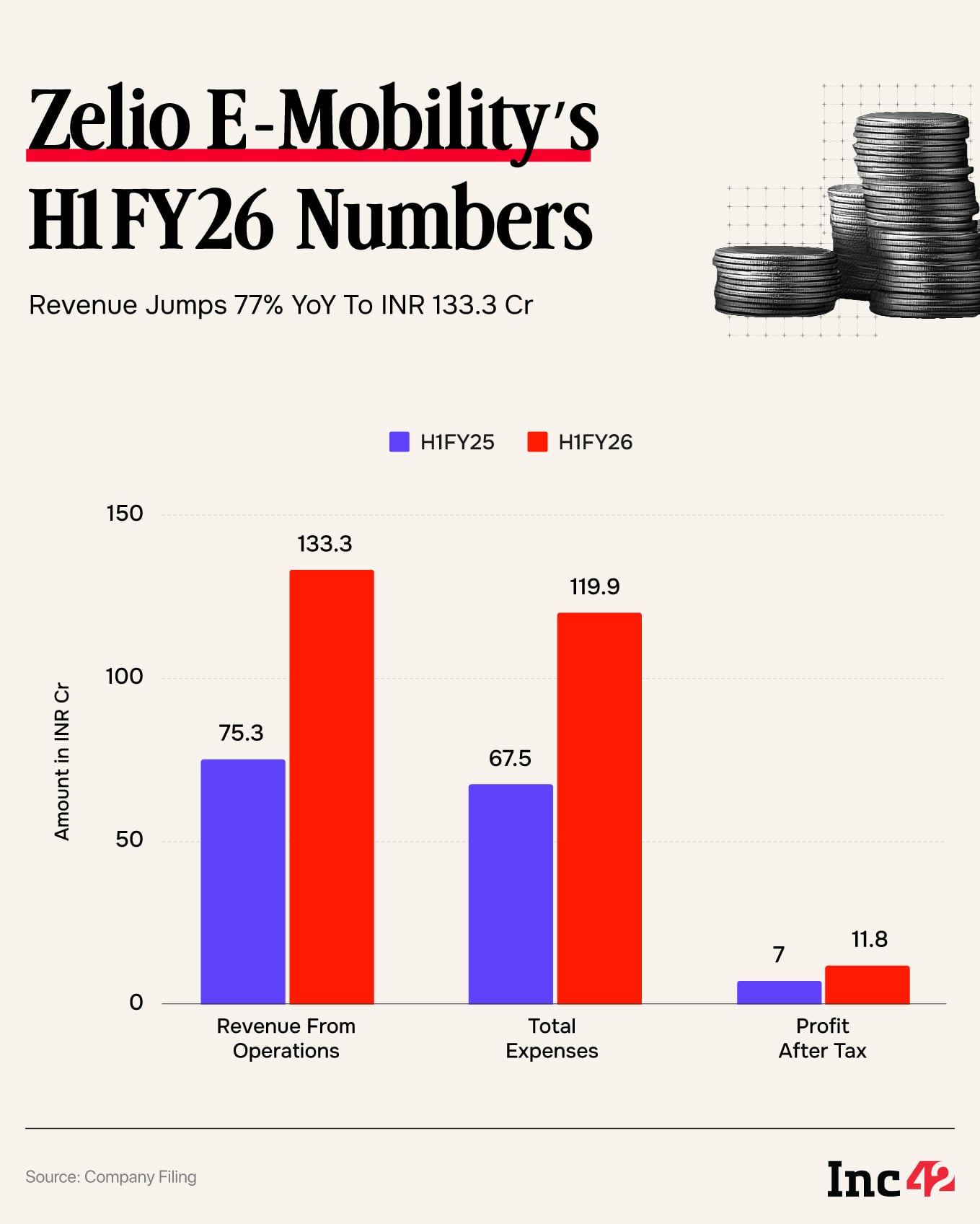

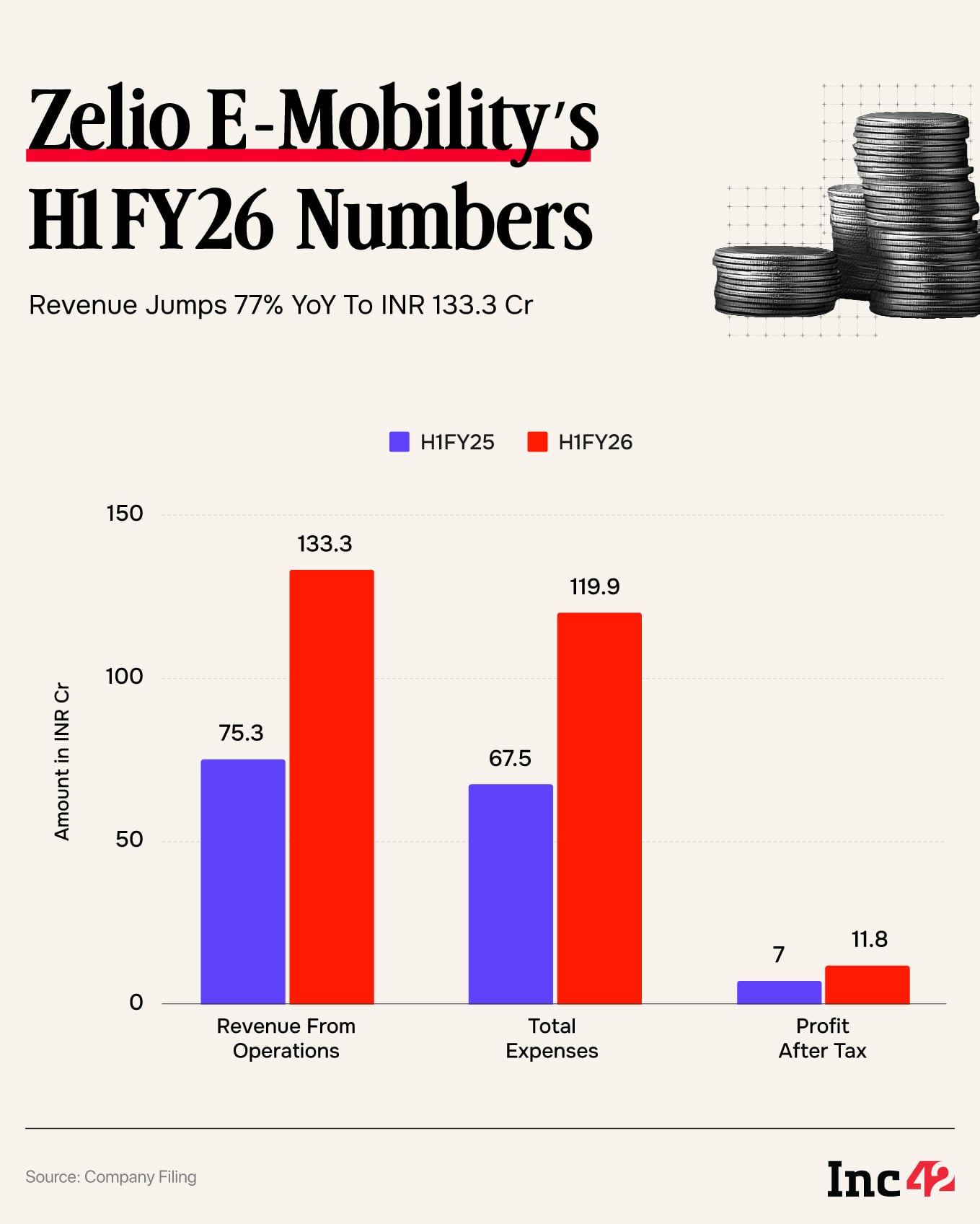

Zelio E-Mobility’s standalone profit for the first half (H1) of FY26 jumped 69% to ₹11.8 Cr from ₹7 Cr a year ago. On a sequential basis, the company’s PAT increased 33% from ₹8.9 Cr.

Operating revenue for the six-month period under review zoomed 77% on-year and 38% on-quarter to ₹133.3 Cr. With other incomes of ₹97.9 Lakh, the company’s total income for H1 of FY26 stood at ₹134.3 Cr, while total expenses for the period surged 78% to ₹119.9 Cr.

In 2025, Zelio went listed on the BSE SME platform. Its IPO proceeds were used primarily for debt repayment, capacity expansion, and working capital support. The listing also brought greater transparency and governance – important in a sector crowded with private, venture-backed companies.

Zelio claims it does not rely on government subsidies, which insulates it from policy volatility as incentives taper over time. “The market is maturing and people are beginning to understand which brands will last.”

Building Trust, Not Banking On Blitz

At the heart of Zelio’s strategy lies a simple belief: in India’s EV market, trust spreads through people, not through publicity.

Zelio has invested heavily in its dealer ecosystem. The company has dedicated sales, service, and dealer-relations teams across India. Service engineers are appointed in a fixed ratio – one for every 30 dealers – and tasked to conduct monthly visits for training and troubleshooting.

To ensure the availability of spare parts, Zelio set up a separate entity – Zelio Auto Company – focussed solely on parts distribution. This ensures that dealers are never left waiting for critical components. “We always say that if sales grow slower, that’s okay. But service can never fail,” Arya said.

Zelio’s strongest markets remain North and East India, across Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh. The company is now doubling down on southern states of Tamil Nadu and Telangana, where EV adoption is accelerating.

Competition, Arya believes, will only intensify. But he remains focussed on execution, rather than making noise. “There’s a difference between selling scooters and building a brand,” he said. “A brand takes years.”

For now, Zelio’s ambition remains firmly rooted in India. Exports may come later, but the immediate goal is to become an everyday electric mobility brand for the country’s mass market, quietly, steadily, and without shortcuts.

[Edited by Kumar Chatterjee]

Source link